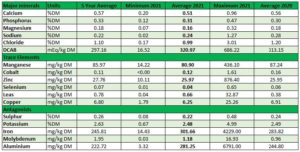

Although there are reports of plentiful grass silage stocks for the majority of farmers, due to the unsettled weather at the start of the season, many had to delay silaging and therefore the quality of silage is variable. Understanding mineral supply from the whole diet, including forage, is important to ensure diets are balanced correctly to optimise animal health and performance. Table 1 shows mineral analyses of over 600 grass silages and given the weather conditions this silage season ranging from very hot and dry, to very wet, some samples may have contamination with soil. So, watch out for antagonists when feeding out this winter.

Antagonists:

Antagonism poses many issues for livestock due to the interference with uptake, availability and competition for absorption sites of minerals required meaning that daily requirement is not fulfilled. Major changes and considerations for the season are:

• Iron: increased in this year’s grass silage at 301.66mg/kg DM compared to the 5-year average of 245.81mg/kg DM. Although grass is a great source of iron, excess iron can act as a pro-oxidant and in freshly calved cows, this can increase the incidence of retained placentas. This will put more stress on the animal’s requirement for selenium and vitamin E as these act as antioxidants. Excessive iron in the diet can also impair the uptake of copper, phosphorous and cobalt.

• Aluminum: Level have shown the biggest change from the 5-year average at 222.72mg/kg DM, to 281.25mg.kg DM. High levels of aluminium have been shown to depress the utilisation of dietary phosphorus and iron. It will be important to check the phosphorus status of livestock to ensure we can prevent deficiency. Symptoms include weight loss, muscle weakness and stunted growth.

• Molybdenum: An increase in this year’s average at 1.18mg/kg DM compared to the 2020 average of 0.96mg/kg DM. Areas that experience high molybdenum levels should remain vigilant as to the effects of molybdenum toxicity and subsequent copper lockup, which can manifest as secondary copper deficiency. Use the Cu:Mo ratio on forage mineral analysis reports to determine the level of risk.

Considerations for different livestock classes:

Dry Cows

-The average DCAB value has increased, due to a large drop in chloride from an average of 1.20% DM in 2020, to an average of 0.99% DM this year. This should be taken into consideration when formulating dry cow diets based on grass silage when opting for a DCAB or partial DCAB approach. If the DCAB level is too high, then there may be an increased risk of milk fever and associated metabolic disorders.

– Calcium levels have declined somewhat from the 5-year average to 0.51% DM so should be better for the formulation of low Calcium transition diets.

Fresh Cows

– This year’s grass silage shows lower average mg levels of 0.16% DM, a 0.02% drop on both the 2020 and 5-year averages. It is important to note the large variation in levels, with levels as low as 0.07% DM reported. Low magnesium can lead to hypomagnesemia (grass staggers). The requirement for both calcium and magnesium in early lactation is increased due to high milk yield and decreased dry matter intakes, so forage should be analysed, and rations balanced accordingly.

Lactating Cows

– For optimal performance of lactating cows, adequate trace mineral supplementation avoiding both deficiency and toxicity is essential. A notable difference in grass silage this season is the decrease in manganese. Green forage usually has high levels of manganese; however, it is important to remember that the proportion absorbed from the diet may be as low as 1%. Often overlooked, manganese deficiencies during gestation increase the risk of long bone deformities in the developing foetus.

– Supplementation is particularly important within the fourth and fifth months of gestation to reduce this risk. Careful consideration should be given to alternative sources to maximise uptake by the animal.

Heifers & Youngstock

– Average copper levels have reduced this year to 6.25mg/kg DM, a 0.66mg/kg DM decrease from last year’s average. It will be important to monitor antagonist levels in forages to ensure that there is no interaction between copper, molybdenum, and sulphur and that the increased iron levels are not competing for absorption sites due to the role copper plays in growth and reproduction.

– Recent studies have shown that although high copper levels do not affect growth rates, they do impact upon expression of oestrus and the number of inseminations in youngstock. This can also have detrimental effects further into lactation as copper accumulates and is stored in the liver, which can prove fatal if released all at once under stressful situations.

Sheep

– Lower average selenium levels have been reported in this year’s grass silage, although selenium levels are generally low in forages. Low selenium levels may result in, reduced immunity, reduced antioxidant capacity, white muscle disease, poor growth rates and poor reproductive performance, on pregnant ewes and growing lambs.

– Supplementation of both inorganic and organic selenium should be considered to ensure optimised uptake into the bloodstream. Selenium supplementation should be considered alongside Vitamin E.

Summary

Overall, this winter we can expect a plentiful supply of forage, with early cuts generally being of better quality. Keeping up with regular (every 2-3 weeks) forage analysis will help keep an eye on silage quality and adjust additional feed rations accordingly. Ensuring healthy, well-fed sheep, healthy cattle and the best possible milk yield.

Practising responsible mineral supplementation by considering mineral supply from the diet and the on-farm situation. Analysing forages for their mineral content allows for greater accuracy in balancing the ration mineral supply against specific livestock requirements. Sources of trace elements also require careful consideration due to varying chemical structures which influence solubility, reactivity, and bioavailability of nutrients.